In spite of the coming disruption to the labour market, the essential skills identified by reports from bodies like the UK’s National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) and the World Economic Forum have remained unchanged for years: collaboration, communication, creative and critical thinking take the top spots – as they did at least as far back as 2007, when they were packaged as the ‘Four Cs’ of 21st century learning. No one could argue against the importance of such skills, but education can articulate what they might look like for 2030 and beyond.

It is tempting, but mistaken in my view, to separate skills into permanent, mutually exclusive ‘human’ and ‘AI’ categories and direct students to master the former. Instead, skills are better conceived as lying on overlapping webs: AI models may be more proficient in some skills and humans in others right now, but many skills – and certainly the four identified above – will be best realised by humans and AI working together as co-workers or classmates, learning from each other’s strengths and weaknesses. Ethan Mollick’s Co-Intelligence: Living and Working with AI (2024) outlines this argument especially convincingly.

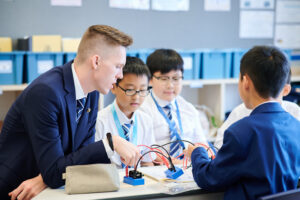

With this in mind, we could support our pupils in navigating the uncertain years ahead by bringing AI into the teaching of essential skills in our classrooms. Developing collaboration might involve teachers designing activities that require the use of an AI model as a member of a team, with students assigning it responsibilities and tasks that they cannot complete alone. Using AI to rewrite original work for different audiences – press releases, research papers, exam-style essays, etc. – would expand pupils’ communication skills considerably, as would building their own collection of effective subject-specific prompts for their AI of choice. Creativity – long thought the preserve of humans alone – has the potential to be enhanced dramatically through AI, not only through the creation of images (Midjourney, DALLE-3), code (Devin), music (Suno, Udio) and video (OpenAI’s coming release of Sora) but also through idea generation, which AI excels at in quantity if not always in quality. And AI can provide limitless questions, counter-arguments, and extension material, strengthening students’ critical thinking further.

Using AI in this way would not only build pupils’ familiarity with current models but also demonstrate the power of expertise. Spend enough time with an AI and you quickly realise its limitations – its overuse of certain words and phrases, its training data bias, its tendency to hallucinate (invent information) rather than admit ignorance.

AI outputs require a level of expertise in a subject area: you can only spot errors in a ChatGPT essay on Macbeth and Banquo’s relationship if you have a good understanding of the Scottish Play overall. Fears of over-reliance on AI and a plague of plagiarism are well-founded but can be partly alleviated by guiding pupils through appropriate use of AI models, and showing the value of deep subject knowledge. The alternative, as many of us will have already seen, is that students use AI out of sight, badly, with little or no awareness of its limitations.

Preparing for this new technological frontier means bringing AI into both the formal and skills curriculum, so that students are exposed to its enormous benefits and sizeable shortcomings at appropriate ages and stages, and with expert oversight. This is no easy task, requiring us as teachers to upskill ourselves quickly and stay abreast of continual developments in the field. But the need is urgent. At last year’s World Economic Forum’s Growth Summit, economist Richard Baldwin put it starkly: “AI won’t take your job – it’s someone using AI who will take your job”. AI in the classroom is frightening. It’s also necessary.

Click the button below to continue reading:

Source of Article:

This blog post is from Education Matters, Volume 1 – Issue 2, published by AISL Academy, p 38-41.

References

- Dickerson, A., Rossi, G., Bocock, L., Hilary, J. and Simcock, D. (2023). An analysis of the demand for skills in the labour market in 2035. Working Paper 3. Slough: NFER.